THE SWEDISH ARCHAEOLOGISTS AND THE CRITICS

We all know that Beowulf was a Geat. It’s also pretty commonly acknowledged that the Geats ruled over territory that lies somewhere in present-day southern Sweden. The territory of the Geats was separate and distinct from the territory of the Swedes,1 who inhabited Svealand with its ancestral power base of Uppsala at the time of the poem’s events. Conventional wisdom suggests that the Geats were equivalent to the Götar who hailed from Götaland and who are sometimes referred to as the Gautar or Goths. Götaland still exists as a distinct region within present-day Sweden (as does Svealand) even if the 1500 year-old tribal associations are now long gone.

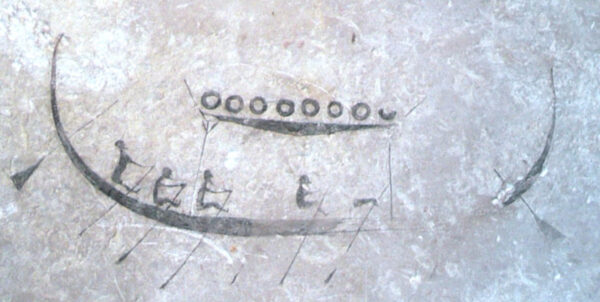

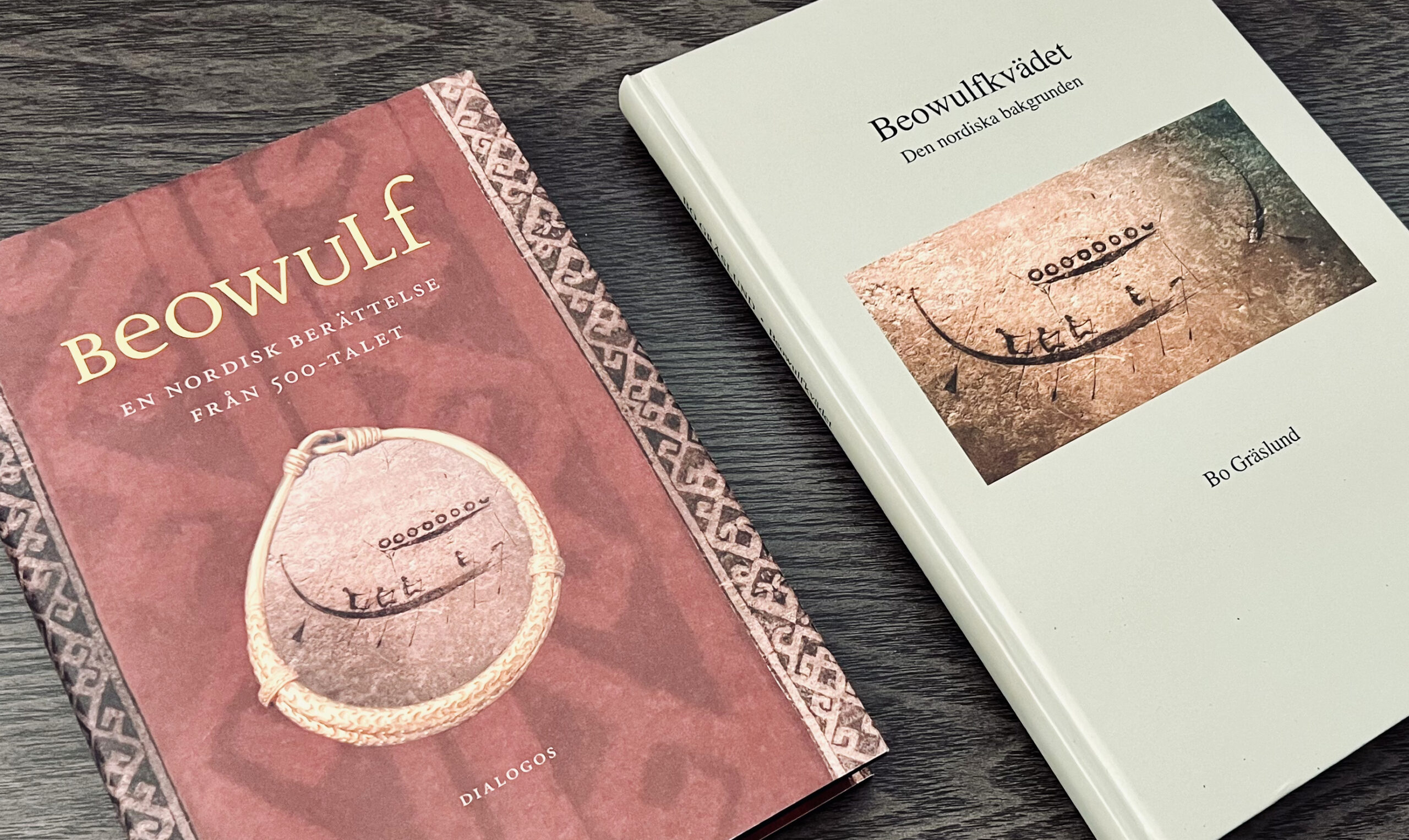

But recently, Bo Gräslund, professor emeritus of archaeology at Uppsala University, has put forward a theory in which he posits that the Geats were not the Götar/Gautar/Goths from Götaland, but the Gutes from the island of Gotland, which is also now a part of the nation of Sweden. Gräslund’s treatise on the subject, Beowulfkvädet: Den nordiska bakgrunden, is an imposing tome, released in 2018 by the Royal Gustavus Adolphus Academy for Swedish Folk Culture and no longer in print (but available to download for free here). However, it was translated to English and released by Arc Humanities Press as The Nordic Beowulf in 2022. In 2023, Gräslund released a reworking of Rudolf Wickberg’s 1889/1914 Swedish translation of the poem to incorporate his theories about its background and to provide his own additional commentary via the Swedish publishing house, Dialogos. Notably, this new translation consistently refers to Beowulf’s tribe as Gutar—Swedish for “Gutes”—throughout whereas Wickberg’s original referred to the Geats as Götar. Unlike Gräslund’s analytical book on the subject, this updated translation is easily found in its home country. Walk into any regular, non-specialty bookstore in Stockholm and there’s a good chance it’ll be on the shelves.

And that comment gets to the heart of the matter of this post: word of Gräslund’s theory has spread like unfettered dragon-fire in his home country while it seems to have gone almost entirely unnoticed in the Anglophone world. This is evidenced not only by the proliferation of his reworking of a classic Swedish translation of the poem, but also by his theory’s widespread acceptance among other archaeologists in Sweden and the depth to which it has pierced Swedish media.

Jonathan Lindström, a Swedish archaeologist, and Kristina Ekero Eriksson, a Swedish science writer with a background in archaeology, both regard Gräslund’s theory as up to snuff in their recent, respective books, Sveriges långa historia (“Sweden’s Long History”) and Vikingatidens vagga (“The Cradle of the Viking Age”). Additionally, SVT (Swedish public television) dedicated an episode of Vetenskapens värld (“The World of Science”) to Gräslund’s theory. Titled Sanning i sagorna (“Truth in the Sagas”), the episode featured interviews of the man himself as well as Kent Andersson (another prominent Swedish archaeologist), Lotte Hedeager (a prominent Danish archaeologist), the aforementioned Kristina Ekero Eriksson, Rachel Burns (a scholar of medieval literature at Oxford), and even Benjamin Bagby (a great performer of Beowulf who I was lucky enough to witness in action once).2 And as recently as October 15th, 2024, the authors of I Beowulfs spår (“In the Steps of Beowulf”) hosted a discussion about their book in the Gold Room of Historiskamuseet in Stockholm, which is Sweden’s foremost history museum; the Gold Room is literally full of gold artifacts. I Beowulfs spår is about the location on Gotland that Gräslund has identified as the likely spot where Beowulf’s mead hall would have once stood: Stavars hus at Stavgard in southeastern Gotland.

Hwaet?

To start, I think there’s a bit of a dynamic playing out in which the enthusiasm in Sweden is indicative of a small nation that now realizes it can make grand, new claims about one of the world’s most famous works of literature.3 Meanwhile, the English-language establishment remains aloof and cynical because that’s what the English-language establishment does. It’s almost like the two opposing factions are debating the outcome of a glorious swimming contest, but without directly addressing one another. Plus, no one outside of Sweden is really paying much attention, anyway.

In general, Gräslund’s theory seems to have gone over extremely well with his fellow Nordic archaeologists, but historians and literary researchers from both Sweden and the broader international community remain more skeptical in the rare instances where commentary can be found. Just to be clear, I’m not a Beowulf scholar, and I’m not claiming to have reviewed all of the documentation pertinent to Gräslund’s theory (let alone the entire corpus of Beowulf scholarship), but I’ve noticed a general pattern. Some exceptions not withstanding, there appears to be something of a dividing line between archaeologists with expertise in Nordic geography versus historians/literary scholars.4

But that also relates directly to one of Gräslund’s points—that Beowulf has been studied for so long from the same general perspective that the scholarship has turned into something of an echo chamber building off certain unproven assumptions that were laid down long ago in days gone by.

Lo—

While I personally find Gräslund’s assertion that the Geats were Gutes to be the most intriguing facet of his treatise, it’s not the only one. In fact, his foundational claim is that the poem was composed in Sweden by a pagan rather than in England by a Christian. With this claim, he’s basically breaking the mead-benches of 100+ years of Beowulf scholarship.

He uses archaeological evidence found in Sweden and a corresponding absence of archaeological evidence found in England to support the claim, essentially asserting that there is no way an English poet could have known such vivid and accurate details about pre-Christian Scandinavian life and material culture at the time of the poem’s earliest possible rendition in the Old English language. He suggests that the poem traveled with a skald from the Uppsala region as part of an entourage that accompanied the bride-to-be of King Raedwald of East Anglia. So, basically, Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo helmet traveled together from Sweden to England (crossing the narrow Anglian isthmus rather than sailing around Jutland).

With that point made, he proceeds to make his argument regarding the Geat issue. He’s not the first researcher to suggest that the Geats were Gutes and openly notes that Gad Rausing, another Swedish archaeologist (and Tetra Pak packaging empire mogul), made the same observation earlier. Gräslund bases his argument on the geographic descriptions found in the poem and how they match up to the physical features of Gotland. Gotland is an island across the “wide water” that features a seawall and razed hillfort as described in the poem as well as place names that correspond to the scene of Beowulf’s death and his burial site. Furthermore, the location of Hrothgar’s hall on the island of Zealand is also theoretically identified—not at Lejre, but at Broskov near the cliffs of Stevns Klint (the poem mentions that the Geats pass sea-cliffs en route to Heorot). A stone road matching the description from the poem and dated to the correct time period has been found at Broskov.

Gräslund additionally backs this up with an argument that the Old English word “weder” that the poem often uses in reference to its Geats might not actually have anything to do with “weather” (as in “Weather-Geats” or “Storm-Geats”) but is actually an old word for ram (the animal). This was first suggested by yet another Swedish archaeologist, Sune Lindqvist (who excavated the famous burials at Valsgärde), and Gräslund points out that the symbol of Gotland has been a ram going back to at least the Middle Ages, and possibly even to the Bronze Age. Furthermore, he explains that the Götar/Gautar/Goths and the Gutes all stem from the same original tribe and that the term for ram was eventually adopted as a signifier to differentiate the people who lived on the island of Gotland from those who lived in Götaland before the tribal identities fractured apart into the divisions that existed at the time of Beowulf’s events.

Beyond these two key arguments, Gräslund also makes some interesting suggestions that, as he notes, are less grounded. Among these is that Grendel might be a metaphor for the famine that resulted from the devastating 536 volcanic eruption and that Grendel’s mother might be a metaphor for the continued famine that resulted from the eruptions in 540 and 547. These are the eruptions that many researchers think gave rise to the story of the Fimbulwinter, the horrific three-winters-in-a-row that precede Ragnarök, when the world ends in fire in Norse mythology.

Gräslund also suggests that a real-life Beowulf may have traveled to Heorot to advise a real-life Hrothgar to take the same measures employed in Gotland to lessen the suffering that resulted from the famine: basically, by drawing lots and expelling people. Gräslund thinks that Beowulf could have been based on the figure of Avair Strabain who features in the Guta Saga, a medieval text that covers the legendary early history of Gotland but that never seems to receive much attention outside of Sweden. Lastly, Gräslund suggests that the dragon is a metaphor for the fire and destruction that the Swedes leave in their wake when the wars with the Geats start up again.

So.

As I’ve already mentioned, I’m not a Beowulf scholar. I can’t read Old English (or Old Norse for that matter). But I do have good familiarity with Swedish geography and have lived in the region of Östergötland, which, prior to the publication of Gräslund’s analysis, would have simply been translated as “Eastern Geatland” by almost everyone (and I’m actually guilty of doing that after the publication of Gräslund’s analysis as may be witnessed in full glory here: Geatland Forever).

I’m not here to don my battle gear for either the for- or against- camps regarding the theory but instead to attempt to share it with people beyond Sweden and to offer a few observations and thoughts, primarily on the matter of the Geats being Götar/Gautar/Goths or Gutes because this is the facet that struck me as the most fascinating. It’s a theory that, if true, would explain a question I’ve long wondered about the Swedish-Geatish wars: how does the identity of the Geats relate to the Swedish-Geatish wars as described in Beowulf, which seem to generally be regarded as having some genuine historical basis?

It never struck me as particularly convincing that the Geats would be the Götar/Gautar/Goths if we are to believe that they were on the losing end of a series of struggles during the time frame in question (6th century) that left them devastated and subservient to the Swedes. There’s a lot of black holes here, but it seems that the Götar/Gautar/Goths continued to hold their own against the Swedes till sometime during the Viking Age several centuries later.5 Götaland did eventually come under the full sway of Svealand but this is only first truly apparent after the close of the Viking Age with the rise of the new nation of Sweden. Interestingly, the central figure in the consolidation of the new nation’s power at that time, Birger Jarl, hailed from Östergötland.

However, it seems that Gotland actually did fall under Swedish control during the time period of Beowulf’s Swedish-Geatish wars. And Gräslund points out that the Guta Saga includes a passage in which the Gutes are defeated by the Swedes and broker peace as a new Swedish tributary. The saga’s timeline for those events is murky, but plausibly coincides with Beowulf’s time frame.

Beyond this, the identification of Gotland’s geographic features that match those of the poem strike me as compelling. Yet, if we take the descriptions of Beowulf’s home so literally, shouldn’t we perhaps take the descriptions of Denmark just as literally, too? And while Gräslund provides some insight into this matter as well, it strikes me as a bit selective. The identification of Broskov and Stevns Klint as possibly being the home territory of the Spear-Danes’ haunted hall is exciting. But what about the location of the mere where Grendel and his mother lived? When Beowulf and his entourage go in search of Grendel’s mother somewhere not-so-far from Heorot, the poem’s language almost makes it seem as if they are ascending the Misty Mountains or entering into one of Caspar David Friedrich’s wilderness scenes, which doesn’t exactly mesh with the geography of the Danish island of Zealand. This is a country where the tallest mountain doesn’t even exceed an elevation of 200 meters. And the mightiest hills are on Jutland anyway, not the island of Zealand where Beowulf’s monster-slaying action takes place.

So how seriously should the poem’s geographic descriptions be taken? Maybe the description of the route to the monsters’ lair is just an exaggeration; the poem mentions cliffs and high points after all, and the locations Gräslund has identified conform to that. But perhaps the context related to elements of pure fantasy (such as inhuman monsters) in the poem are likewise given fantastical descriptions? But that just brings me to another question: what about all the research about Beowulf that states Beowulf (the man) is really just one incarnation of an ancient folkloric motif that sometimes, if not always, connects to animalistic, supernatural, and/or magical elements?

Therein seems to be a pretty notable conundrum. Regardless of Beowulf’s identity as a Göt/Gaut/Goth or as a Gute, was he based on a real person? Gräslund and other Swedish archaeologists seem to think there is a very real possibility of that. Historians and literary scholars do not.

Bro!

In 2023 Tom Shippey released his own translation of Beowulf in modern English (ironically, the same year that Gräslund released his in Swedish, but fate goes ever as fate must). As Leonard Neidorf notes in the volume’s introduction, Shippey is the only scholar to have both extensively studied the poem itself—publishing numerous interpretative analyses of it—and to now, at last, have also translated it. Early in his career Shippey published “The Fairy-Tale Structure of Beowulf” in the academic journal, Notes & Queries, in which he explains how the character of Beowulf follows and deviates from certain folkloric patterns found throughout ancient European literature and legends. 50 years and many publications later, Shippey released Beowulf and the North before the Vikings, which is one of the few English-language publications of any sort to acknowledge Gräslund’s work.

Beowulf and the North before the Vikings is a very informative volume, but Shippey’s brief refutal of Gräslund’s Beowulf-is-a-Gute theory relies on an interpretation of Nordic geography that I personally found less convincing than Gräslund’s. The refutal also falls back on the notion that the Götar/Gautar/Goths succumbed to the Swedes in the 6th century. For reasons stated above, that doesn’t make sense to me, but then again, the historical record is very small. Perhaps Shippey is right.

It has emerged with clarity to me that Gräslund knows his Migration Period/Vendel Period archaeology and Nordic geography while Shippey knows his Old English language and heroic Germanic literary traditions. And while both dabble in fields outside their own, that’s not where their expertise lies. Both are preeminent scholars in their respective fields and both have released translations and interpretations of Beowulf very recently, but they passed like ships in the night (on the whale-road, of course).

So what would a conversation between Gräslund and Shippey on this subject be like? Have they ever corresponded with one another? Would they be able to see one another’s point of view and have a productive conversation? Would Shippey find fault in Gräslund’s understanding of the poem’s language or would Gräslund find fault in Shippey’s understanding of the Nordic geography/archaeological record? Would such a discussion result in a toasting of ale cups or a storming of swords?

All I know is that I’d like to see such a discussion or a collaborative article or something along those lines, where these two viewpoints attempt to work together to find a common ground, if one can be found. Likely that’s just wishful thinking on my part, but with that, my thoughts are at least very consistent with much of the existing commentary on Beowulf!

Footnotes

- We refer to this ancient tribe as “Swedes” in English, but in Swedish they were the “Svear” (hence the name of Svealand for their home territory, also sometimes called Svearike and Svitjod depending on the specific point in time under discussion and the tributary lands included/excluded, but delving into those distinctions is not the purpose here today). If you are interested in knowing more about the Svear and their burial mounds, please check out this PDF of my article “Glory in Death: Sweden’s Magnificent Pre-Viking Graves” that appeared in Medieval World: Culture and Conflict. ↩︎

- The same episode also included a vignette about shield maidens and an interview with Leszek Gardeła, the Polish archaeologist who wrote Women and Weapons in the Viking World: Amazons of the North and edited The Norse Sorceress: Mind and Materiality in the Viking World. ↩︎

- Beowulf has never been as well known in Sweden as in the UK or US. Victoria Dyring, the SVT broadcaster who introduces Sanning i sagorna, openly admits that she’d never even heard of the poem before beginning work on the documentary about Gräslund’s theory. ↩︎

- Beyond those mentioned in the body of this post, other Swedes who have viewed Gräslund’s theory favorably include Rune Edberg, an archaeologist at Stockholm University, who wrote favorable commentary for a publication of Sigtuna Museum, and the poet, Magnus Ringgren, who wrote a favorable review of Gräslund’s theory for Aftonbladet. Dissenting Swedes include Dick Harrison, Sweden’s biggest celebrity historian, who wrote a scathing op-ed about Gräslund’s theory for Svenska Dagbladet. Christian Lovén, a historian for Riksarkivet (the Swedish National Archives) argued against Gräslund’s theory in Fornvännen: The Journal of Swedish Antiquarian Research. Outside of Sweden, Christopher Abram, professor at the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame, wrote a skeptical review of Gräslund’s book for the journal, Arthuriana. Tom Shippey argues against the theory in his book, Beowulf and the North before the Vikings, which is discussed more in the body of this post. ↩︎

- For more on the history of the Götar/Gautar/Goths, I can’t recommend Mats G. Larsson’s Götarnas riken: Upptäcktsfärder till Sveriges enande highly enough. Besides providing an engaging overview of the relevant Vendel Period and Viking Age history and archaeology of Götaland, he also makes keen observations about the identity of Beowulf’s Geats. Much of this has to do with the distinctions between the Västgötar (Western Götar) and Östgötar (Eastern Götar) and how they and their territories related to the Svear (Swedes). In particular, there has been a long strand of generally disproven thought in Sweden that obsesses over the status of Västergötland called the Västgötaskolan. It mainly attempts to identify Västergötland as the ancestral power base of the present-day nation of Sweden (as opposed to the Uppsala region) but has also ventured into Beowulfian waters, attempting to claim the Geats as their own, seeking to identify the hero’s grave and equate the Västgötar to Weder-Geats. An insightful man, Larsson actually poses the notion that perhaps there was no such tribe as the Geats and that the poem simply presents a muddle of ethnic identities that got distorted over time and distance. ↩︎

Subscribe to get updates from Scandinavian Aggression!

You know, if you feel like it or whatever. Your email is only used to send updates when new nonsense has been posted to the site. It's stored in the secure abyss of WordPress and not shared anywhere or anyhow else. Skål som fan!

Great piece. There is an excellent review by Christian Lovén in FORN VÄNNEN Journal of Swedish Antiquarian Research 2019/2. Lovén welcomes Gräslund’s book, but does not support the Gotland theory, mainly on the basis of criticism of the linguistic arguments about names. Dagfinn Skre, in his excellent book The Northern Routes to Kingship, is also very supportive of Gräslund’s approach, but disagrees with the Gotland thesis on archaeological grounds. Both Lovén and Skre favour Västergotland as Beowulf’s home. Lovén has even managed to match up a placename in Beowulf (hreosna næs) with a site on the Göta älv not too far from Bohus Castle called Mareberget, earlier (1276) recorded as Horsa berg. Hreosna, otherwise unrecorded in Old English, perfectly matches Old Norse hryssa, mare.

Keep up the good work!

Oops. A tiny correction. The placename in Beowulf is hreosna beorh, (not hreosna næs), which is an even closer match with Maraberget/Horsa berg. It’s at line 2477.

Thank you! I appreciate the kinds words and your comments–I had seen this Fornvännen spat between Lovén and Gräslund but this is the first I’ve heard of Skre’s book. Looks worth checking out. I think this all aligns with a major point of my post here though–the historians and the archaeologists don’t agree! And the Nordic historians are paying a little more attention than those of the Anglophone world. I’m also aware Dick Harrison (Sweden’s top tv celebrity historian) tore it apart in an article for Svenska Dagbladet (though I haven’t read that as I can’t get past the paywall). It’d be interesting to see a historian/language expert sit down with an archaeologist and have a productive discussion…in which they’re both willing to admit where gaps in the record or methodology exist in their respective fields.

The geography is the most interesting part to me. I like Lovén’s suggestion that Östergötland be investigated more too.