© Archäologisches Landesamt Schleswig-Holstein

The Danevirke is generally well-known among viking enthusiasts: it’s the earthen fortification built along the southern border of what was once Denmark. Archaeological evidence suggests that it was first constructed in the 400s or 500s before being reinforced and expanded during the Viking Age as part of a famed effort to prevent the Carolingian Empire from invading. Ironically, the Danevirke now lies entirely in Germany. We have Otto von Bismarck to thank for the shifting of the border, but that’s beside the point.

The point is that there’s a similar structure in the Swedish county of Östergötland, but rather than having become a UNESCO World Heritage Site like the Danevirke, it instead lies across the landscape like a lifeless snake, completely forlorn and mostly forgotten.1

Remnants of the Götevirke stretch between the lakes of Asplången and Lillsjön. With a length of 3.5 kilometers, it’s only a fraction of the Danevirke’s much more imposing 30 kilometers. And its history is murkier.

The Götevirke only received its name in the early 20th century when Oscar Almgren, a Swedish archaeologist openly inspired by the magnificence of the Danevirke, coined the term. It makes sense—the structure is, like the Danevirke, a virke (a generic “works” sometimes used with defensive connotations) located in Östergötland, one of the two historic Götaland regions (the other is Västergötland).

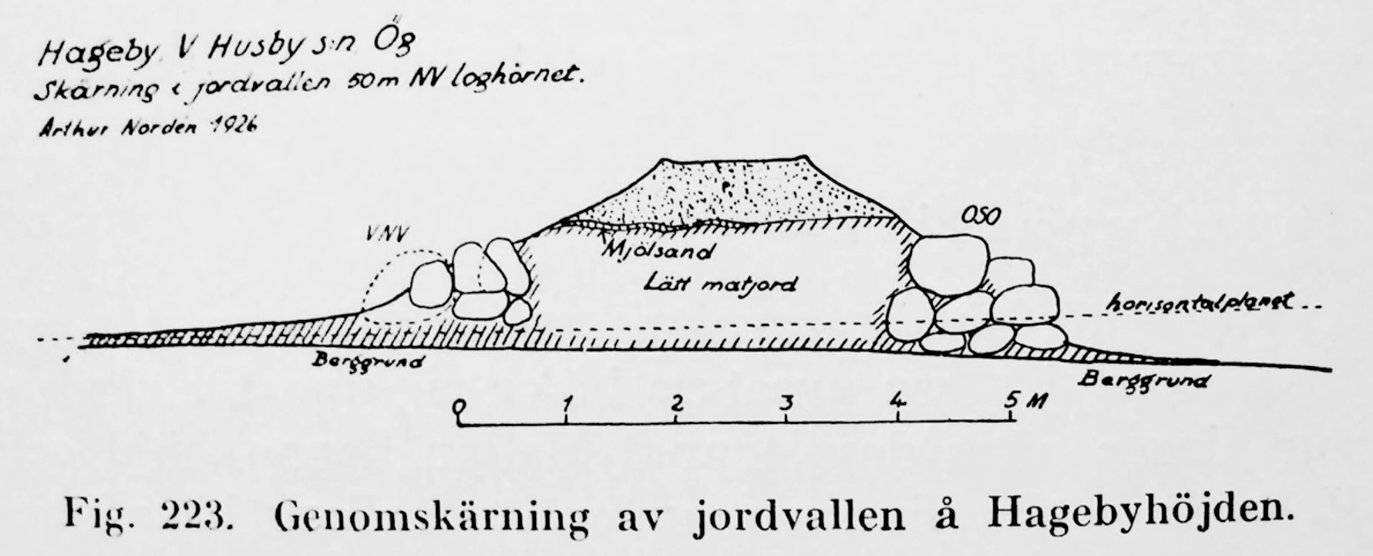

Another Swedish archaeologist, Arthur Nordén, excavated a portion of the Götevirke in the 1920s and drew some pretty grand conclusions. He declared that the fortification had been built in the early 6th century as a ward against incursions from the Swedes. During the 6th century, the Swedes (or Svear)2 ruled the historic core of their territory north of Lake Mälaren and likely some tributary lands, but their rule didn’t yet extend into Götaland, which was ruled by the Götar. Basically, Nordén wanted to prove that the Götevirke and some hillforts in its vicinity fit the description of the defensive structures used by the Geats in Beowulf during its recounting of the Swedish-Geatish wars. This notion, of course, rests on the assumption that the Götar were in fact the Geats of Beowulf, which brings us to one of my favorite subjects: the dastardly identity of the Geats.

There is no solid consensus as to who the Geats were. The Götar have been the leading contender for a very long time, both in Sweden and outside of Sweden, but the Gutar from the island of Gotland now have a serious claim to the Geatish identity throne thanks to the recent research of Bo Gräslund. Please check out my previous post, Beowulf the Gute?, if you want to know more about that.

At any rate, it’s now accepted that Nordén was wrong, not necessarily about the identity of the Geats (which remains a source of eternal debate), but about the dating of the Götevirke. After Norden’s excavation, the structure experienced 70 years of neglect, but was then excavated again in the 1990s with updated techniques. The more recent excavation revealed that the Götevirke was constructed during the Viking Age, several centuries after Nordén believed. If you want to know more about the archaeological history of the Götevirke and some of the other, more fanciful theories about its construction (which really run the gamut), Länsstyrelsen Östergötland has an informative video about here: Göta Virke – en försvarsanläggning (yes, it’s in Swedish only).

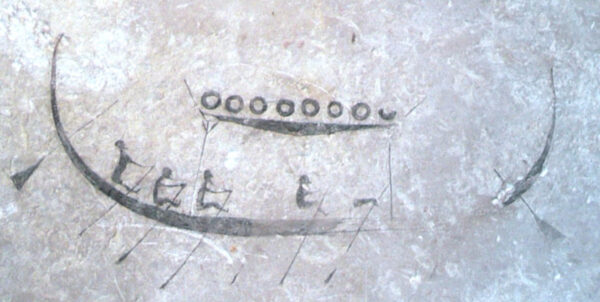

Still, no one knows exactly who built it or exactly when it was built. It’s safe to say that the Götevirke was part of a system of defense structures intended to protect the interior of Östergötland from seaborne attack, but that’s about it. It never achieved a legendary status similar to the Danevirke in the historic record, and the past millennium hasn’t exactly been kind to it. The most visible, easy-to-access portion of the Götevirke to visit today is fenced in on a farm beside a country road. And the informational sign about it, at least at the time of my visit in August of 2024, was in a state of total disrepair. But, as the saying goes, Gǣð ā Wyrd swā hīo scel!

- And of course there are other similar structures elsewhere, too. Östergötland and Schleswig-Holstein are not the landscapes to be blessed with the presence of such defensive border structures. ↩︎

- For more on the Svear and their ancestral territory, check out my article from Medieval World: Culture and Conflict called “Glory in Death.” ↩︎

Subscribe to get updates from Scandinavian Aggression!

You know, if you feel like it or whatever. Your email is only used to send updates when new nonsense has been posted to the site. It's stored in the secure abyss of WordPress and not shared anywhere or anyhow else. Skål som fan!