Outside of the Kingdom of Sweden, Östergötland isn’t particularly well known, but it does possess one unique claim to fame especially for Norse nerds and ancient literature aficionados: it’s probably-maybe-could-be the Land of the Eastern Geats. The relevance here is, of course, Beowulf. Östergötland ostensibly translates as Eastern Geatland, just as Västergötland ostensibly translates as Western Geatland. Traditionally, Västergötland has held the favored position for being home of the Geats described in Beowulf, but that’s far from proven, and the island of Gotland is another contender for the ancestral Geatish homeland. It’s a murky mess that I’ve discussed before, but suffice it to say: there are a lot of fascinating historical sites in Östergötland.

This post focuses on a handful of some of the sites found along the western fringe of the territory. Östergötland is largely comprised of fertile farming land that stretches between the Baltic Sea in the east and Lake Vättern in the west. Läke Vättern is Sweden’s second largest lake and serves as the dividing line between Östergötland and its larger neighbor of Västergötland. Eastern Östergötland possesses more unique traces of defensive fortifications intended to protect the territory’s heartland from seaborne attack and most likely hosted the Battle of Brávellir—one of the most epic battles from the sagas—if it ever took place. Western Östergötland, on the hand, harbors more evidence of ancient wealth. It’s in western Östergötland that we find one of Scandinavia’s most famous runestones, the iconic pendant of Freyja, and one of Sweden’s largest ancient stone monuments.

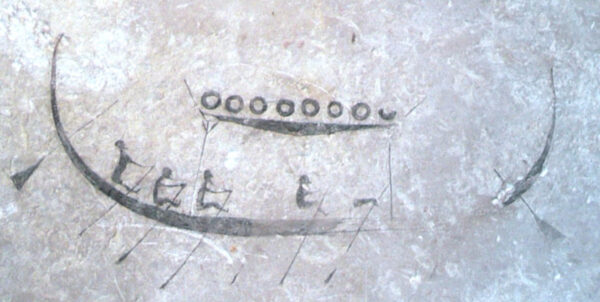

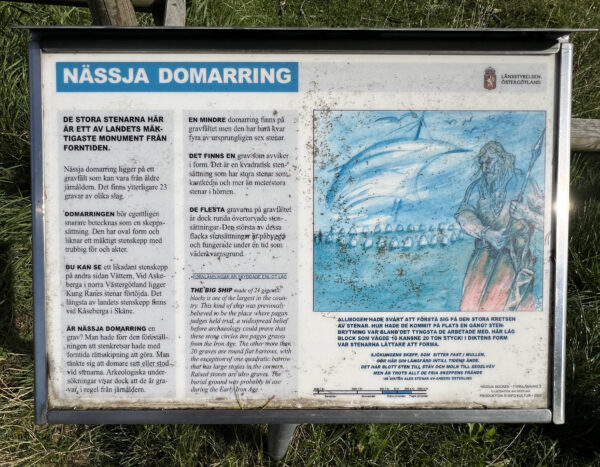

Nässja Domarring

Nässja Domarring is one of Sweden’s largest stone monuments and is located in Nässja parish within the city limits of Vadstena, a quaint lakeside Swedish city that figures more prominently in Swedish history after the conversion to Christianity. Nässja Domarring also possesses a confusing matter of identification: it is labeled as a domarring (circle of stones) and is often referred to as a skeppssättning (a more oblong oval of stones resembling a ship) but Länsstyrelsen Östergötland prefers the term stenkrets (also a circle of stones, but with less specificity than domarring—the layout of the Nässja monument most strongly resembles the outline of a meadhall). Semantics aside, it’s an impressive monument measuring 44 meters in length by 18 meters in width and dates to the early Iron Age. And, of course, there are dead people buried here.

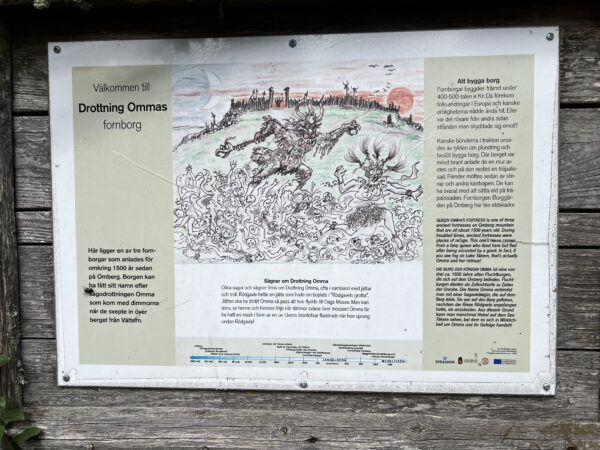

Drottning Ommas Fornborg

Fornborg means “ancient fortress” and is usually translated in English as “hillfort,” specifically referencing hilltop fortifications built in the Bronze Age and Iron Age in Europe. This one lies atop a cliff overlooking Lake Vättern, and one must say, it’s seen better days. It’s just one of three that exists at Omberg, a lonely mountain covered in woods that divides the lake from the flat interior farmlands of Östergötland. Dating to the 5th century, the fortress is named after the legendary Queen Omma who supposedly attracted the undesired lust of a creepy giant, so she fled her defensive fortification and disappeared into the fog of Lake Tåkern just a couple of miles to the east of the site.

Rökstenen

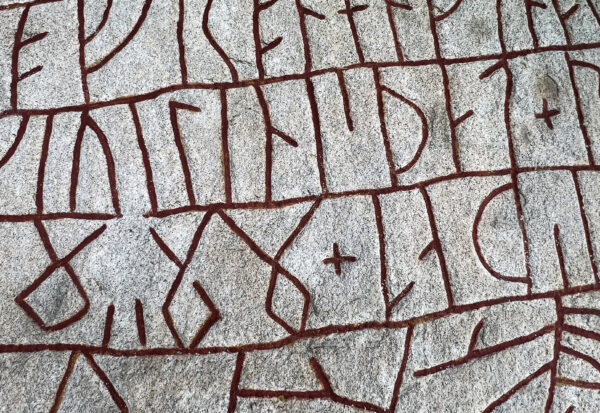

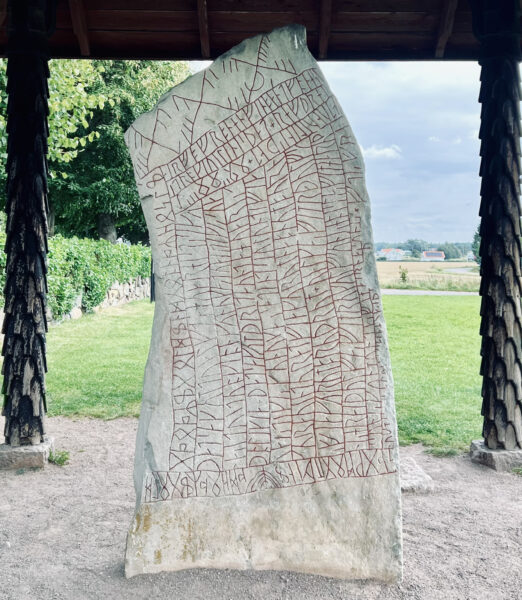

About five miles inland from Lake Vättern is Rökstenen, the Rök Stone, one of Scandavia’s most famous runestones as well as one of the largest. As with so many relics from the Viking Age and earlier, it sits at a rather unassuming spot: on the grounds of a rural parish church surrounded—yes—by more of Östergötland’s flat fertile farmland. Dating to the 9th century, the Rök Stone’s inscription is quite a bit older than that of most runestones, which date to the 11th century. Much has been said and written about the Rök Stone’s meandering story arc that features the deaths of sons and possible suppositions of Fimbulwinter, so I’m not going to rehash all of that here and instead will refer those of you who are interested to this page hosted at the University of Gothenburg which includes some recent research on the stone and its media coverage in English.

Östergötlands Runinskrifter 137

Just down the road from the imposing Rök Stone is this little and much lesser-known stone at Kvarntorp that dates, like most runestones, to the 11th century. It provides an amusing contrast to the Rök Stone, because its runes are complete and total nonsense—the informational plaque provided by Riksantikvarieämbetet (the Swedish National Heritage Board) even goes so far as to state that the carver only had a dim notion of how the runes should even look.

Kungshögabacken Gravfält

Carrying the spirit of the aforementioned carver of Östergötlands Runinskrifter 137 into our own era is the present-day scenario found at Kungshögabacken in Mjölby, which lies about fifteen miles from the shore of Lake Vättern. As an extensive gravfält, or “grave field,” Kungshögabacken hosts about 125 graves, the earliest of which are 4000 years old. The site also hosts numerous ancient stone momument configurations as well as skålgropar (indentations carved into stone surfaces during the Bronze Age). But the real kicker is that Kungshögabacken now also hosts a frisbee golf course that quite literally winds its way through the surviving remnants of this ancient site. On the one hand, Kungshögabacken is a site that clearly suffers from severe disrespect. On the other, it also offers visitors the opportunity to play the coolest round of frisbee golf on the planet, so there’s that, I guess.

Askahögen

Last but not least is Askahögen (the Aska Mound) in Aska parish about one mile east from the center of Vadstena. Long thought to be a burial mound on a scale similar to the Royal Mounds of Gamla Uppsala, the Aska Mound is now recognized as having been the foundation of a massive meadhall thanks to the research of Martin Rundkvist. Aska is best known as the location where the famous circular pendant of Freyja was found in a presumed völva’s grave. More on this specific location is to come later this year in Medieval World: Culture and Conflict!

Subscribe to get updates from Scandinavian Aggression!

You know, if you feel like it or whatever. Your email is only used to send updates when new nonsense has been posted to the site. It's stored in the secure abyss of WordPress and not shared anywhere or anyhow else. Skål som fan!